Preprint ban, ancient DNA and funder pressure

Fossil DNA hints at mysterious Toalean folks

The 7,000-year-old skeleton of a teenage hunter-gatherer from Sulawesi in Indonesia is perhaps the first remains found from a mysterious, ancient culture known as the Toaleans. Sulawesi has among the world’s oldest cave artwork, however ancient human stays have been scarce there.

The largely full fossil of a roughly 18-year-old Stone Age lady was present in 2015, buried in a limestone cave.

DNA extracted from the cranium means that she shared ancestry with New Guineans and Aboriginal Australians, in addition to with the extinct Denisovan species of ancient human.

“This is the first time anyone’s found ancient human DNA in that region,” says Adam Brumm, an archaeologist on the Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution at Griffith University in Brisbane, who’s a part of the group behind the discover (S. Carlhoff et al. Nature 596, 543–547; 2021).

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

The authors say she could also be one of many Toalean folks, whose existence is understood from scant archaeological proof, reminiscent of notched stone instruments, and who’re thought to have lived in Sulawesi across the identical time.

The stays had been discovered with Toalean-type instruments, offering robust proof of the lady’s hyperlink to those little-known folks, agrees archaeologist Shimona Kealy on the Australian National University in Canberra.

Preprint ban deemed ‘plain ludicrous’

Australia’s main analysis funder has dominated greater than 30 fellowship functions ineligible as a result of they talked about preprints and different non-peer-reviewed supplies, sparking an outcry from scientists who say the transfer is a blow to open science and will stymie careers.

At a time when the COVID‑19 pandemic has introduced using preprints to the fore, researchers say the stance by the Australian Research Council (ARC) — which limits candidates’ potential to discuss with the newest analysis — is out of step with trendy publishing practices and at odds with abroad funding businesses that enable or encourage using preprints.

Researchers have taken to Twitter in outrage, calling the blanket ruling “short sighted”, “plain ludicrous”, “cruel”, “astonishing”, “outdated” and “gut-wrenching”.

Nick Enfield, a linguistic anthropologist on the University of Sydney, who’s presently funded by the ARC, argues that the choice is unconscionable and unethical. “The leading research-funding body of the country is potentially throwing away valuable research on a ridiculous technicality,” he says.

The ARC didn’t reply particular questions from Nature about its rationale for excluding preprints, or verify what number of candidates had been deemed ineligible in consequence, however a spokesperson stated that the rule “ensures that all applications are treated the same”, including that “eligibility issues may arise in a number of ways”.

In tweets on 30 August, the ARC responded to the complaints, saying it had “commenced a rapid review” of its coverage.

Funders pressure researchers to suppress outcomes

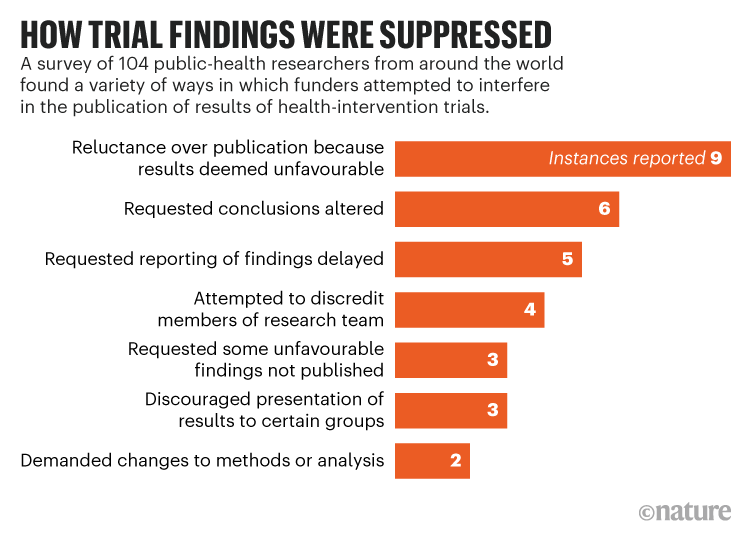

A survey of public-health researchers has discovered quite a few instances of trial results being suppressed on subjects reminiscent of diet, sexual well being, bodily exercise and substance use, with 18% of respondents reporting that they’d, on not less than one event, felt pressured by funders to delay reporting, or to change or not publish findings.

The survey concerned 104 researchers from areas together with North America, Europe and Oceania who’ve led trials to judge behavioural interventions designed to enhance public-health outcomes (S. McCrabb et al. PLoS ONE 16, e0255704; 2021). These trials, printed between 2007 and 2017, had been cited in Cochrane opinions, thought of the ‘gold standard’ of proof used to tell health-care decision-making.

Public-health analysis has a historical past of {industry} interference, so the authors, led by Sam McCrabb on the University of Newcastle in Australia, anticipated industry-funded research to be these most affected. “But we didn’t find any instances of that,” she says.

In the survey, trial investigators had been requested if they’d encountered suppression, starting from requests to vary strategies or alter conclusions by to appeals to delay publication or not launch outcomes.

The authors discovered that respondents had been most certainly to report pressure from government-department funders looking for to affect analysis outcomes.