The father of the cellphone

The father of the cellphone

There wouldn’t be Uber or Lyft or Google Maps or FaceTime or Instagram or Tinder or Snapchat or TikTok or iPhones or Android phones if someone hadn’t invented the cellphone. Fortunately, somebody did.

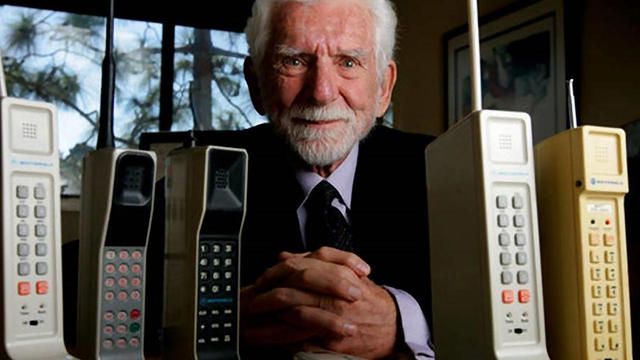

It was Marty Cooper. “I know a lot about the future, ’cause I spend all my time there,” he laughed, “when I should be thinking about practical things of today.”

Cooper’s memoir, “Cutting the Cord” (Rosetta Books), tells the story. He is a Chicago native, Navy submarine officer, and, eventually, an executive at Motorola, maker of police and military radios – and in the early 1970s the two-way radio known as the car phone.

Those early car phones were not cellular telephones: “They had one transmitter in a city, and a very limited amount of radio channels,” Cooper told correspondent David Pogue. “The chances were one in 20 that you could make a phone call, that’s how bad that service was.”

In 1972, the idea of a cellular network was catching on, in which cities would be divided into smaller land regions (called cells), each with a transmission tower. As you moved from cell to cell, your call would be handed off from one tower to another.

AT&T, Motorola’s much bigger rival, asked the FCC for a monopoly on cellular communications, not because it had a vision of phones in our pockets, but to expand its car phone business.

Cooper said, “They were gonna take over our business as well as this whole new thing, and do it wrong! People had been wired to their desks and their kitchens for over 100 years, and now they’re gonna wire us to our cars, where we spend five percent of our time.”

Motorola wanted to prove that opening up the airwaves to competition would spur more innovation.

“So I thought about, ‘How could we do a dazzling demonstration? The only way to do it is to have a working … something,'” Cooper said.

Cooper’s team began with the design, not the technology: “Small enough to put in your pocket, big enough so that it could go between your ears and your mouth,” he explained.

He showed Pogue a model of the early design. “This isn’t a miniature – this is what they actually had in mind? It’s a tenth the size of the final one,” Pogue marveled.

By the time Motorola had added the battery and all the circuitry, it grew to this size:

In only three months, Marty Cooper had overseen the construction of a working cellphone. Cooper named it the DynaTAC. “You could talk for 25 minutes before the phone ran down,” he said.

On April 3, 1973, Cooper made the world’s first public cellphone call, as a demonstration for a reporter.

“So, we met this guy on Sixth Avenue in New York, in front of the Hilton,” he recalled. “And then I had to make a phone call to demonstrate it.”

And whom did he call? Joel Engel, his archrival over at AT&T. “And I said, ‘Joel, I’m calling you on a cellphone, but a real cellphone, a personal, handheld portable cellphone.’ Silence on the other end of the line.”

Cellphone inventor Marty Cooper on making his first public call:

Cooper’s gambit worked. The FCC was so impressed that it opened the cellular industry to competition.

Cooper left Motorola in 1983; since then, he and his wife Arlene Harris, a tech inventor in her own right, have started a series of companies in the cellular industry.

Pogue asked, “Isn’t the general advice for relationships not to work with your spouse?”

“We don’t agree about everything,” Cooper said. “But you know, that’s the spice of life, is disagreement – as long as it’s friendly.”

Pogue asked Cooper, “But it seems like, if there’s a technological dispute, can’t you just go, ‘I’ll have you know I’m the father of the cellphone!’ Wouldn’t you automatically win?”

Harris deadpanned, “No.”

The cellphone has come a long way, but Cooper thinks that we’ve only begun to tap its potential: “We are only at the very, very beginning. We are going to revolutionize mankind in many ways. I believe that the whole process of education is going to be revolutionized. And the other revolutions that are gonna happen is in health care. I know I sound like an optimist, but poverty is going to be a thing of the past.”

Already, Cooper said, workers in poorer countries use their cellphones to move money around without needing a bank. “This has stimulated entrepreneurism. People’s lives are being saved. People are being moved out of poverty.”

Cooper is a notorious fitness buff. At 92, he lifts weights and takes walks, sometimes on the beach in front of his home. But he considers mental exercise even more important.

“If you don’t keep learning all your life – keep an open mind, soak up stuff, be curious – you lose the ability to learn,” he said. “And to me, that’s the scariest thing of all.”

As for his new book, well, Hollywood has already bought the film rights. Pogue asked, “Who’s gonna play you in the movie?”

“I was hoping that you would do it, David,” he laughed. “You’re the only star that I know.”

“Have your people talk to my people,” Pogue said. “Here’s what I find strange, Marty: I know this is a stereotype, but as a 92-year-old guy, I might expect you to relish the stories from the past more than the stories of the future.”

“Well, I have observed that things in the past have continued to improve, you know?’ Cooper replied. “People are richer today. They are healthier today. We’ve still got a lot of problems, but there’s no reason to think that we aren’t gonna keep improving.”

For more info:

- “Cutting the Cord: The Cell Phone Has Transformed Humanity” by Martin Cooper (Rosetta), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon and Indiebound

- Follow Martin Cooper (@MartyMobile) on Twitter

- dynallc.com

Story produced by Michelle Kessel. Editor: Emanuele Secci.