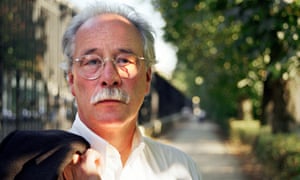

Revealed: the secret trauma that inspired German literary giant

WG Sebald’s writing on the Holocaust was driven by the anger and distress he felt over his father’s service in Hitler’s army

His books are saturated with despair. Over and over again, his emotionally traumatised characters are caught – inescapably – in plots that doom them to a life of anguish. Often, they kill themselves.

Now, the psychological wounds and suicidal thoughts that blighted WG Sebald’s own life and secretly inspired him to begin writing fiction are to be laid bare for the first time in a forthcoming biography.

“What lay behind his writing was this great trauma that he was expressing and suffering,” said Carole Angier, author of Speak, Silence: In Search of WG Sebald, the first major biography of the German author who wrote The Emigrants and Austerlitz.

The book, which will be published later this month, sheds new light on why Sebald often chose to write about the Jewish and German tragedy of the Holocaust.

Lauded as one of the world’s greatest writers when he died aged 57 in a car crash 20 years ago, Sebald always had a troubled relationship with his father, a German soldier who fought in the second world war, the biography will show.

He fought with his father – an “old-fashioned authoritarian man” – his whole life, but their relationship took a turn for the worse when, at the age of 17, Sebald was shown a film at school about concentration camps. It was the early 1960s, and at the time, Angier says, “the Holocaust was never spoken of in German families. That was Sebald’s first visual and visceral encounter with it.”

The film traumatised him. “He saw his father as a Nazi, who had served without question in Hitler’s army.”

Painfully aware that his parents had accepted and benefited from Hitler’s rule, he began to find their silence on the subject agonising. “He could never get his parents to talk about the war,” Angier says. “He would accuse his father, and his father would clam up and say he didn’t remember. Then he would get angry and they would have a row.”

At around the same time, Sebald – who was brought up as a Catholic – began to question the church. “He became a dissenter.”

He grew depressed and eventually had a breakdown. “He said later he came ‘close to the edge of his reason’ at this time, and that this can happen if someone’s identity that’s been built up over many years is destroyed or falls to bits,” Angier says.

He would later explore these feelings in Austerlitz, his final masterpiece, about a Jewish refugee whose parents perished in the Holocaust. Adopted by Christians after arriving in Britain on the Kindertransport as a small child, the refugee discovers his Jewish identity on the brink of adulthood and then, after repressing the trauma of what happened to him, has a nervous breakdown later in life.

Sebald hid his own breakdown from his family and never sought any formal treatment. He continued to suffer from serious episodes of depression, anxiety, panic and “terrible feelings of isolation” throughout his life, and ended up having three major breakdowns in total, the biography reveals for the first time.

The second occurred during his first term as a 22-year-old teacher at Manchester University. Overwhelmed by his feelings of alienation, hopelessness and panic, Sebald fell into another “acute depression”, similar to that of the narrator of Max Ferber’s story in The Emigrants. “He later confirmed that what he wrote there was true of himself, that he went through a crisis during that time.”

At the time, he confessed to a friend he thought he was “going mad” and that “sometimes he’d like to let go, but there were people who were holding him back”.

Angier assumes this was his family: “I think he was suicidal, or had suicidal thoughts, throughout his life.” It was at this point that he started writing fiction. “He wrote his first novel, which has never been published. The hero is a very gloomy, hypersensitive character. It’s definitely entirely based on himself – it’s a very autobiographical piece.”

It was while he was teaching at Manchester University in his early 20s, in this vulnerable state that he got to know the first Jewish person he had ever met, his “wonderful” landlord, Peter Jordan, a German refugee. “Here was a real person, who had grown up exactly like him, spoke his language, lived in the same way, skied on the same hills – and he’d had to flee and his parents were murdered. Meeting him brought home to Sebald the human reality of these terrible crimes.”

Sebald – who, by this time, had started calling himself Max, instead of Winfried, his Nazi-approved birth name – was struck by one particular aspect of Jordan’s behaviour. Like Sebald’s parents, Jordan did not like to speak about the war.

“He did that typical refugee thing of not thinking about it, not facing what happened to his parents. That is the story that Sebald is always telling, of these people who are both the survivors and victims of Nazism, forced into exile, carrying a burden for the rest of their lives and trying not to think about it, to avoid trauma.” In Sebald’s books, however, this strategy never works.

Later, he wanted to reproduce in his readers the same sense of shocking reality he had felt, so he put photos of Peter Jordan and his family in The Emigrants and pretended they belonged to his fictional character Max Ferber. “The character’s history is the history of Peter Jordan and all the photographs are of his family,” Angier reveals.

Sebald’s final breakdown, at the age of 35, was the most severe. On a journey through Italy, he started to imagine men were pursuing him around Verona with murderous intent. “He felt absolutely terrified and convinced that all these terrible, sinister things were happening around him.” He feared he was going mad, an experience he recounts in his first published work of fiction, Vertigo. “He was in a very, very disturbed state.”

He tells a friend later that when he visited Milan cathedral, he got to the top and “nearly fell into the abyss”.

It was this breakdown that “tipped him over” into serious writing. “That breakdown was crucial. It is then that he begins to write literary fiction. He fills his characters with his own despair.” Writing fiction allowed him to express the trauma he was feeling and hiding from the world. “He always said he only started to write to get away from his academic routine. That was not true. He started to write to explore and deal with this terrible depression that he’d fallen into. And it wasn’t wholly personal, in fact the main trauma was the historical burden he was carrying.”

But Angier is keen to point out that his books also display his deadpan sense of humour. “People think his books are incredibly pessimistic and gloomy, which they are, but he was also mordantly funny. Humour was a coping mechanism – a socially acceptable way of expressing his gloom. And he was very charming and funny in real life.”

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or by email-ing jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org