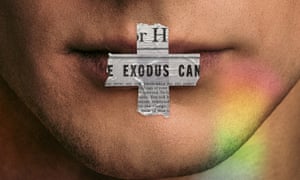

‘It doesn’t leave you’: the toxic toll of LGBTQ+ conversion therapy

Netflix documentary Pray Away, exec-produced by Ryan Murphy, traces the history of conversion therapy with regretful leaders of the “ex-gay” movement

Julie Rodgers was 16 years old when her mother introduced her to Ricky Chelette, the “singles minister” at a Baptist church in Arlington, Texas, who coached LGBTQ+ youth on how to “change” their sexuality. The high school junior had recently come out to her parents; Chelette, a man with “same-sex attractions” married to a woman, was brought in to fix what was seen as a problem. As Rodgers recounts in Pray Away, a new Netflix documentary on the “ex-gay” movement within western Christianity, and her book Outlove: A Queer Christian Survival Story, Chelette preached an enticing, insidious gospel of change: that Rodgers’ attraction to women was due to an insufficient bond with her mother as a child, that such attractions could be neurologically altered by committed study, that to do otherwise would be a disappointment to God and the community that had formed the backbone of her life to date.

Rodgers was one of at least 700,000 people in the United States to undergo “conversion therapy” – treatments, counseling, and community that pressures LGBTQ+ people to “change” their sexuality, and a belief system exposed with searing lucidity in Pray Away. The 100-minute film, directed by Kristine Stolakis and executive produced by Ryan Murphy and Jason Blum, examines the destructively common practice and its larger “ex-gay” movement, often led by LGBTQ+ people who themselves believed they had changed, several of whom later renounced their teachings.

As the film outlines, conversion therapy is neither a specific practice nor singular movement; it’s “this complex amalgamation of old pseudo-psychology that’s disproven, the spiritual belief that you don’t have a place in God’s kingdom if you don’t change, and then this culture that surrounds you with these messages that are inescapable”, Stolakis told the Guardian.

Pray Away focuses in particular on Exodus International, the non-profit, inter-denominational organization founded in 1976 by five evangelical Christians, which propelled and popularized the idea that it was possible – and preferable – to change one’s sexual orientation. (The organization’s then president Alan Chambers, who appears in the film, renounced conversion therapy in 2012; Exodus International dissolved in 2013, but an international offshoot, Exodus Global Alliance, continues today.) Several of the movement’s leaders were themselves LGBTQ+ people who professed, with various levels of sincerity, to have changed, offering an alluring roadmap to others vulnerable through shame, self-loathing, and confusion. “The movement provides this very dark but very appealing sense of hope to people who are suffering,” said Stolakis, “and shining a light on that felt key to understand the movement.”

Stolakis was first inspired to investigate the movement by her late uncle, a conversion therapy survivor she described as “like a second dad”, who suffered from medical conditions common to those who passed through the movement: depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, addiction, suicidal ideation. She witnessed first-hand the stickiness of the movement’s ideology of shame and inadequacy, like a corrosive stain.

“It gets into the most intimate parts of your daily life, and it doesn’t leave you,” she said. “Even when you leave a therapist’s office, when you leave your pastor’s office, when you leave that Bible study, that belief system sticks with you. And that internalization of it all is why self-harm is such a big part of this movement, and unfortunately why suicide is such a part of this movement.” As the film notes in its coda, youth who experienced some form of conversion therapy are more than twice as likely to die by suicide.

Pray Away includes numerous figures who were formerly involved in the ex-gay movement, from Exodus co-founder Michael Busse (who left the organization in 1979) to former Family Research Council spokespeople Yvette Cantu and John Paulk. All recount different routes into evangelical Christianity – for Cantu, seeking solace at age 27 after losing friends to Aids; for Paulk, a search for identity and balm to loneliness – that undergirded a taxing, toxic ideology of denial.

The film is not entirely a retrospective; it opens with Jeffrey McCall, a self-described “de-transitioner” who formerly lived as a trans woman, as he canvasses patrons of a Georgia supermarket to hear his story with prayer. The segments with McCall demonstrate how the ex-gay movement’s ideology has continued under a different name, through social media networks rather than through traditional media, with messaging updated to the era of Instagram empowerment. McCall’s “Freedom March” rally could, at first glance, pass as a Pride gathering – diverse crowd, rainbow logos, joyful shouts and music, hollow incantations of diversity, inclusion and acceptance adapted from the LGBTQ+ rights movement. The event is deceptively affirming; as one singer puts it to the crowd: “All these different faces, all these different races, to come and make a stand, to let people know that freedom is here.”

That “freedom” (from being gay) is still one founded in denial, rejection, a baseline belief that anything other than straight is broken and sinful. “A defining part of this movement is that it’s an example of homophobia and transphobia wielded outwards,” said Stolakis. “As long as a culture of homophobia and transphobia continues – in our churches, in our communities, in our country – you will see something like this. People will internalize these beliefs, they will be taught to hate themselves, they will be very compelled to believe that they can change.”

The current assault on trans rights in the US – conservative state lawmakers have proposed 110 anti-trans bills just this year – could be seen as “another iteration of the whole belief system of conversion therapy, because it is saying that to be trans is to be sick”, said Stolakis. “Just like what we saw politically with the ex-gay movement, it has real political implications for other trans people because either directly or indirectly, it supports anti-trans legislation, which we’re seeing become ubiquitous in this country.”

For Rodgers, whose wedding to a woman is included in the film’s final scenes, the toll of ex-gay movement is invisible, personal, years of directing imposed shame inward. “I’ll go back and read old journal entries, and it’s all, ‘God forgive me for having such evil flesh,’” she recalls in Pray Away. “And the only hope for me is that God will save me from myself. I was a teenager, and I was a really good teenager. I just thought I was so bad.”

Given the shame, denial, and social pressure inherent to the movement, the question of individual culpability is tricky; Pray Away concludes with consideration of guilt without tipping into either blame or absolution. “What do you think about the blood on your hands?” Randy Thomas, a former Exodus International leader, recalls someone asking him in the film. “I said, ‘Right now, all I know is I’m afraid to look down at my hands.’”

The aim was to “mix in understanding with accountability”, said Stolakis. “If this were a system of bad apples, then when the individual leaders in my film changed their minds, the ex-LGBTQ movement would’ve been over. That is not the case.”

The question of individual accountability is “something we knew we had to touch on in the film, but to answer it would always be reductive”, she said. “So that’s why we ended the film where we do. But I really hope that people continue to ask those questions and there needs to be understanding and accountability as we all continue to heal from the pain and the trauma of the ex-LGBTQ+ movement.

“How that happens is going to be individual to communities, individual to countries, depending on exactly how this manifests,” she added. “But what I know is that as long as this self-hate is encouraged, some version of this will continue.”

Pray Away is now available on Netflix